The Bibliographic Ontology‘s aim is to be expressive and flexible enough to be able to convert any existing bibliographic legacy schema (such as Bibtex and its extensions, MARC, Elsevier’s SDOS & CITADEL citation schemas, etc.) and RDFS/OWL ontologies to it.

This new BIBO version 1.2 is the result of more than one year of thinking and discussions between 101 community members and 1254 mail messages. The project’s first aim of expressiveness and flexibility is nearly reached. BIBO’s ongoing development is now pointing to a series of methods and best practices for mature ontology development.

Some BIBO mappings between legacy schemas have been developed, but this trend will now be accelerated. More people are getting interested in BIBO’s ability to describe bibliographic resources. Some people are interested in it to describe bibliographic citations; others are interested in it to integrate data from different bibliographic data sources, using different schemas, into a single and normalized data source. This single data source (in RDF) can then become easily queried, managed and published. Finally, other people are interested in it as a standard agreed to by an open community, that helps them to describe bibliographic data that aims to be published and consumed by different kind of data consumers (such as standalone software like Zotero; or such as citation aggregation Web services like Scirus or Connotea).

With this BIBO 1.2 release, much has changed and been improved. Now, it is time for the community to start implementing BIBO in different systems; to create more mappings; and to complete more converters.

Design Redux

As you may recall from its early definition, BIBO has been designed for both: (1) a core system with extensions relevant to specific domains and uses, and (2) a collaborative development environment governed by the community process.

These design imperatives have guided much of what we have done in this new version 1.2 release to aid these objectives.

BIBO in OWL 2

The new version of BIBO is now described using OWL 2. In the next sections you will know why we choose to use OWL 2 as the way to describe BIBO in the future. However, saying that it is OWL 2 doesn’t mean that it becomes incompatible with everything else that exists. In fact, it validates OWL 1.1 and its DL expressivity is SHOIN(D); this means that fundamentally nothing has changed, but that we are now leveraging a couple of new tools and concepts that are introduced by OWL 2.

As you will see below this decision results in much more than a single update of the ontology. We are introducing an updated, and more efficient, architecture to develop open source ontologies such as The Bibliographic Ontology.

New Versioning System

OWL 2 is introducing a new versioning and importation system for OWL ontologies. This feature alone strongly argued for the adoption of OWL 2 as the way to develop BIBO in the future.

This new versioning system consists of two things: an ontologyURI and a versionURI. The heuristics to define, check, and cache an ontology that as an ontologyURI and possibly a versionURI are described here.

BIBO has an ontologyURI and multiple versionURIs such as http://purl.org/ontology/bibo/1.0/, http://purl.org/ontology/bibo/1.1/, and http://purl.org/ontology/bibo/1.2/.

Right now, the current version of the ontology is 1.2. This means that the current version of BIBO will be located at two places: http://purl.org/ontology/bibo/ and http://purl.org/ontology/bibo/1.2/.

The location logic of ontologies is described here. What we have to take care here is that if someone dereferences any class or properties of BIBO, it will always get the description of that class or property from the latest version of the ontology. This is why the caching logic is quite important. The user agent has to make sure that it caches the version of the ontology that it knows.

What is really important to understand is that the URI of the ontology won’t change over time when we introduce new versions of the same ontology. Only the location of these versions will change.

Finally, the OWL 2 mapping to RDF document tells us that we have to use the owl:versionInfo OWL property to define the versionURI of an ontology. This is the reason why the use of this OWL 2 versioning system doesn’t affect the validity of BIBO as a OWL 1.1 ontology; because owl:versionInfo is also an OWL 1.1 property.

Now, lets take look at the tools that we will use to continue the development of BIBO.

Protégé 4 for Developing BIBO

We chose to now rely on Protégé 4 to develop BIBO in the future. We wanted to start using a tool that would help the community to develop the ontology. Considering that Protégé 4 Beta has been released in August; that it supports OWL 2 by using the OWLAPI library; and many plugins are already supported; it makes it the best free and open-source option available.

What I have done is to add some SKOS annotation properties to annotate the BIBO classes and properties to help us to edit and comment on the ontology. Here is the list of new annotation properties we introduced:

- skos:note, is used to write a general notes

- skos:historyNote, is used to write some historical comments

- skos:scopeNote, is really important. It is the new way to target the classes and properties, imported from external ontologies, that we recommend to use to describe one aspect of BIBO. The scopeNote will tell the users the expected usage for these external resources.

- skos:example, is used to give some examples that show how to use a given class or property. Think of RDF/XML or RDF/N3 code examples.

Finally, all these annotations are included in BIBO’s namespace.

OWLDoc for Generating Documentation

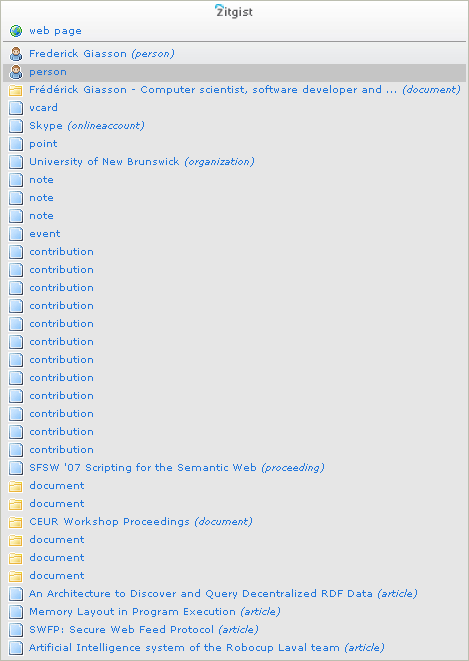

OWLDoc is a plugin for Protégé that generates documentation for OWL ontologies. In a single click, we can now get the complete documentation of an ontology. This makes the generation of the documentation for an ontology much, much, more efficient. Users can easily see which ontologies are imported, and then they can easily browse the structure of the ontology. Many facets of the ontology can be explored: all the imported ontologies, the classes, the object/data properties, the individuals, etc.

You can have a look at the new documentation page for BIBO here. On the top-left corner you have a list of all imported ontologies. Then you can click on facet links to display related classes, properties or individuals. Then you may read the description of each of these resources, their usage, and their annotations (scope-notes, Etc.).

Please note there are still some issues and improvements to do with the template used to generate the pages, such as multiple resource descriptions not yet adequately distinguished. We are in the process of cleaning up these minor issues. But, all-in-all, this is a major update to the workflow since any user can easily re-create the documentation pages.

Collaborative Protégé for Community Development

Now that it is available for Protégé 4, we will shortly setup a Protégé server and make it available to the community to support BIBO’s community development. We will shortly announce the availability of this Collaborative Protégé.

In the meantime, I suggest to use the file “bibo.xml” from the “trunk” branch of the SVN repository (see Google Code below). The Bibliographic Ontology can easily be opened that way using the “Open…” option to open the local file of the SVN folder, or by using the “Open URI…” option to open the bibo.xml file from the Google Code servers. That way, each modification to the ontology can easily be committed to the SVN instance.

Google Code to Track Development

As noted above, the BIBO Google Code SVN is used to keep track of the evolution of the ontology. All modifications are tracked and can easily be recovered. This is probably one of the most important features for such a collaborative ontology development effort.

But this is not the only use of this SVN repository. In fact, it as an even more central role: it is the SVN repository that sends the description of the ontology for any location query, by any user, for any version. Below we will see the workflow of a user query that leads the SVN repository to send back a description for the ontology.

Google Groups to Discuss Changes

The best tool to discuss ontology development is certainly a mailing list. A Google Groups is an easy way to create and manage an ontology development mailing list. It is also a good way to archive and search discussions that has an impact on the development (and the history) of the ontology.

Purl.org to Access the Ontology

Another important piece of the puzzle is to have a permanent URI for an ontology that is hosted by an independent organization. That way, even if anything happens with the ontology development group, hopefully, the URI will remain the same over time.

This is what Purl.org is about. It adds one more step to the querying workflow (as you will notice in the querying schema bellow), but this additional step is worth it.

General Query Workflow

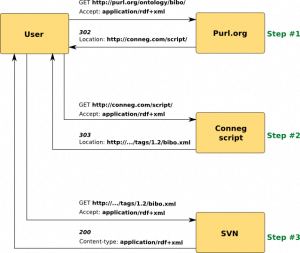

There is one remaining thing that I have to talk about: the general querying workflow. I have been talking about the new OWL 2 versioning system, purl.org redirection and using the SVN repository to deliver ontology descriptions. So, there is what the workflow looks like:

[clik to enlarge this schema]

At the first step, the user requests the rdf+xml http://purl.org/ontology/bibo/. As we discussed above, this permanent URI is hosted by Purl.org; what this service does is to redirect the user to the location of the content negotiation script.

At the second step, the user requests the rdf+xml serialization of the description of the ontology at the URI of the location sent by the Purl.org server: http://conneg.com/script/. One of the challenges we have with this architecture is that neither Purl.org nor Google Code handles content negotiation with a user.

Thus, it is also necessary to create a “middle-man” content negotiation script that performs the content negotiation with the user, and redirects it to the proper file hosted on SVN repository. (If Purl.org or the SVN repository could handle the content negotiation part of the workflow, we could then remove the step #2 from the schema above and then improve the general architecture. However, for the present, this step is necessary.)

Note 1: Take a special look at the redirection location sent back by the content negotiation script: http://…/tags/1.2/bibo.xml. This is a direct cause of the new versioning has the versionURI http://purl.org/ontology/bibo/1.2/. Considering the versioning system, the content negotiation script redirects the user to the description of the latest version of the ontologyURI (which is currently the version 1.2).

Note 2: Purl.org current doesn’t strictly conform with the TAG resolution on httpRange-14. However this should be resolved in an upgrade of the Purl.org system that is underway (the current system is dated as of the early 1990s).

At the third step, the SVN repository returns the requested document by the user with the proper Content-Type.

Conclusion

Developing open source ontologies is not an easy task. Development is made difficult considering the complexity of some ontologies, considering the different way to describe the same thing and considering the level of community involvement needed. Thus, open source ontology development needs the proper development architecture to succeed.

I have had the good fortune to work on the this kind of ontology development with Yves Raimond on the Music Ontology, with Bruce D’Arcus on the Bibliographic Ontology, and with Mike Bergman on UMBEL. Each of these projects has led to an improvement of this architecture. After two years, these are the latest tools and methods I can now personally recommend to use to collectively create, develop and maintain ontologies.